|

|

|

|

|

|

Rock Climbing

Tips |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rock

Climbing Tips —

Beginners and

experts alike

can use these

tips to improve

their climbing

as well as

impress the

onlookers.

If these tips

don’t improve

your climbing as

much as a least

a letter grade,

you can send me

an angry email.

-

Picture

yourself on

a ladder

when you

climb, move

from one

hold to the

next as

relaxed as

if you were

ascending

the rungs or

steps of a

ladder.

-

Avoid over

gripping

holds with

your hands.

You will

quickly tire

your arms

out.

-

Use your

feet like

you would

your hands.

-

Trust your

feet. You

can stand on

your legs

all day. You

don’t hang

with your

arms all

day. Too

often people

hang on

their arms

and then

fall off,

sailing

right past a

monster

ledge they

could have

had their

feet on.

-

Trust your

belayer, and

focus on

climbing. If

you are

worried your

belayer

doesn’t have

you, find a

new belayer

you can

trust.

-

Concentrate

on what is

within

reach.

Sometimes

you can use

an

intermediate

hold (a

smaller hold

between

secure

holds) to

get to a

better hold.

-

Climb from

the bottom

up, not top

down. Of

course, if

you can see

the top of

the route,

look to see

if there is

a pattern

working from

the goal

down to

where you

are, but

when you

start to

climb, focus

on the

climbing at

the bottom

of the route

as you climb

up.

-

Climb in an

X shape with

your hips

being the

middle of

the X. Hang

with your

arm

straight.

Your

skeleton can

take much

more of a

load than

your muscles

can. If the

heel of your

foot is

hanging too

far down you

may notice

your leg

start to

shake like a

“sewing

machine”.

This is very

common

occurrence,

simply apply

more weight

to your toes

so your calf

muscle spasm

can stop.

-

Fear of

heights is

normal.

Climbing is

all about

conquering

those fears.

Time will

cure the

fear of

heights. A

good trick

is to look

down no

further than

your feet to

correctly

place them

on the best

part of the

hold.

-

Take your

time. Climb

like a cat

does—quiet,

deliberate,

and precise.

Picture the

move, and

then execute

it. Use all

of your

limbs, not

just two.

The lower

the angle of

the climb,

the more

time you

have, so use

it. Make

each move as

fluid as

possible

|

|

TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Climbing Ratings — In

the 1950’s a group

called the Sierra Club

modified an old system

which they used to rate

climbs according to

their difficulty. This

system is now called The

Yosemite Decimal Rating

System.

The YDRS breaks climbing

down into classes and

grades. Nearly every

climbing guide uses this

system. Beginning

climbers can use this

system to find climbs

that are challenging but

not too difficult;

preventing them from

venturing out onto

something too hard that

might lead to injury.

All climbing, hiking,

crawling, and so on can

be broken down into

these classes. A brief

explanation of the

classes will describe

what type of climbing

might be encountered.

Class 1:

Walking, on an

established trail.

Class 2:

Hiking, up a steep

incline, possibly using

your hands for balance.

Class 3:

Climbing up a steep

hillside; a rope is not

normally used.

Class 4:

Exposed climbing,

following a ledge system

for example. A rope

would be used to belay

past places where a fall

could be lethal.

Class 5:

This is where technical

rock climbing begins. A

3 point stance (Two

hands and a foot or two

feet and a hand) is

needed. A rope and

protection are needed to

safeguard a fall by the

person leading. Any

unprotected fall from a

class 5 climb would be

harmful if not fatal.

Class 5 climbs are

subdivided into

categories to give more

detail.

5.0-5.4:

Climbing up a ramp or a

steep section with good

holds.

5.5-5.7:

Steeper, more vertical

climbing, but still on

good holds. These routes

are also easily

protected.

5.8 +/-

Vertical climbing on

small holds. A + means

that the climbing is

more sustained like a

5.9, but the route would

still be considered a

5.8. If you see a –

after the 5.8 rating it

means that the climb

only has one or two

moves like a solid 5.8

would have, but more

resembles a 5.7. The +

and – are becoming

outdated and most guide

books have discontinued

their use.

5.9

+/-This

rating means that the

climb might be slightly

overhung or may have

fairly sustained

climbing on smaller

holds. With practice the

beginning climber can

climb in the 5.9 range

quickly and with

confidence.

5.10 a, b, c, d

Very sustained climbing.

A weekend climber rarely

feels comfortable in

this range unless they

do go EVERY weekend or

has some natural talent.

The difference between a

5.10 b and a 5.10 c is

very noticeable. Most

likely the climbs are

overhung with small

holds and are sustained

or require sequential

moves.

5.11 a, b, c, d

This is the world of the

dedicated climber.

Expect steep and

difficult routes that

demand technical

climbing and powerful

moves.

5.12 a, b, c, d

The routes in this range

are usually overhanging

climbs requiring

delicate foot work on

thin holds or long

routes requiring great

balance on little holds.

5.13 a, b, c, d

If you can climb upside

down on a glass window,

these climbs are right

up your alley.

5.14 a, b, c, d

These climbs are among

the hardest in the

world.

5.15 a

This is as hard as

climbing gets, folks.

Keep in mind that very

few climbers can

actually climb at this

level, although

Spiderman eats these

climbs for breakfast.

Climbs are rated by the

hardest move on the

route. A person who is a

solid 5.8 climber

theoretically should be

able to climb through

the crux (the hardest

part of the climb) on

any route rated 5.8

regardless of the type

of rock or area they

climb at. That is the

theory anyway.

Unfortunately, climbs

are not rated by a

committee of climbers so

a particular climb can

be off as much as a

letter grade or more.

Having said that, the

majority of climbs you

will do will be right on

the money.

Since the destiny of

every mountain, cliff,

boulder, or pebble is to

become like the gravel

you walk on to get to

the climb, know that ALL

RATINGS ARE SUBJECTIVE!

Weathering of the rock,

the sun, wind and

extreme temperatures all

contribute to making

climbs harder or easier

than the rating given to

a climb the first time

it is established.

While routes are given

ratings so you don’t

bite off more than you

can chew, try climbing

at your level and then a

little bit more. You

might surprise yourself

and actually get up the

route in relatively good

form.

If you are having

trouble with a

particular climb, don’t

blame the rating. Train

a little harder, do a

few extra pushups at

night, and give it a go

again. Climbing is about

setting goals and

working to achieve them.

The last rating class of

the Yosemite Decimal

Rating System is class

6, which is considered

aid climbing. Aid

climbing has its own

rating system that does

not use decimals like

class 5. Instead it uses

A to abbreviate Aid and

then a number which

indicates how

challenging the moves

are and the commitment

level involved on the

climb.

|

|

TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rock Climbing Shoes —

Climbing shoes are the

most important

investment you can make

as a climber. In order

to reach your highest

climbing potential, you

need to get the right

shoes for your feet.

Shoes are the most basic

equipment for every

climber from the

bare-bones minimum

boulderer to the gear

laden big wall climber.

You might want to

consider making them

your first gear

purchase.

Today’s climbing shoes

are scientific wonders

compared to the antique

shoes of a decade ago.

Sophisticated sticky

rubber, cushioned soles,

synthetic leathers and

anti-fungal treatments

are just a few of the

many options available

for you to choose from.

To begin, you need to

understand how a

climbing shoe is made,

and then you can find

one that fits your foot.

That’s right, not every

shoe was made for your

individual foot, so

let’s turn away from all

the glitter and smoke

and look inside the

shoe.

Climbing shoes are made

around a “last.” A last

is a piece of wood or

plastic shaped like a

foot, much like a

mannequin’s foot that

models sandals in a shoe

store. Shoe

manufacturers take that

last and sew the inside

of the shoe around it.

That shell is covered

with the outside leather

of the shoe and then the

sole is glued on, laced

up and put on your foot.

Every manufacturer of

climbing shoes has their

own set of lasts. Some

are shaped like your

feet, others like your

climbing partner’s feet.

To find the right shoe

to fit your foot, you

have to try a bunch on.

When you are just

learning how to climb

you will want a “board

lasted” shoe. This is

just what it sounds

like, the soles on these

types of shoes are quite

stiff allowing the

beginner to learn how to

edge and smear.

Once you teach your feet

how to move you can get

a shoe with a more

supple sole that will

allow you to feel those

miniscule holds under

your pinky toes.

However, you’ll want to

keep those hard soled

kickers around if you

ever do a multi-pitch

climb—your toes will

thank you for the

breathing room.

Make sure you go to a

quality rock climbing

store to try on climbing

shoes. Be patient and

take your time. Listen

to the sales person,

they will help you.

Beware of stores that

don’t have at least some

small holds for you to

practice edging on. You

can’t get a feel for

your shoes if you don’t

try them on and practice

edging in them. Try on

at least three different

brands before buying,

because again, every

manufacturer uses a

different last.

When you lace up your

shoes for the first

time, leave room to lace

them tighter. As you

break in your new shoes

the material will

stretch and you’ll need

some room to tighten the

laces. Slippers (shoes

without laces) are not a

recommended starting

pair of shoes, though

most boulderers and gym

climbers prefer them for

the ease of a quick on

and off. Shoes with

laces allow you to

tighten them in

different places to dial

in a perfect fit. Don’t

let your friend talk you

into a certain brand of

shoes unless your feet

are identical twins of

his feet, though you

might find a different

model from the same

company that will fit

your foot.

Finally, take care of

your new shoes and

they’ll last you a long

time. Leaving them in

the back of your car on

a hot summer day or by a

camp fire can make the

soles come unglued. Dirt

and mud will make your

feet skid on holds, so

take a tarp or crash pad

to launch off of onto

the rock. It is best to

fit and climb in your

shoes without socks to

get the sensitivity your

toes need on the rock.

The rewards of properly

fitted shoes are happy

feet for years to come.

|

|

TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Climbing Falls — What

goes up… that’s right —

must come down. Whether

you are just starting

out or you are a pro,

you are going to fall

off of a route

somewhere, sometime (I’m

so optimistic).

Psychologists tell us

that we are born with

two fears: the fear of

loud noises and the fear

of falling. It is a very

natural thing to not

want to fall off a rock

climb, but if you climb,

you will fall. Falling

shows you where you need

to improve. It is a

great motivator to train

harder so you don’t have

to take the drop.

Basically, if you climb

rocks, you will take a

fall sometime and

somewhere. Alright, with

that out of the way, we

can now learn how to

fall in a way that you

will not likely get

injured. First of all,

wear a helmet. Second,

anticipate when on the

route you will most

likely fall. As you look

up at the route, you can

usually tell where the

crux will be; a

prominent overhang, a

spot without many

features (climbing

holds), etc.

Keep in mind that as you

fall you won’t always be

traveling straight down.

Traversing (moving

horizontal to the last

place you clipped in the

rope) will create a

pendulum effect with the

fall. Falling on an

overhang will send you

down and back into the

rock. And falling onto a

ledge, a bulge in the

route or the ground,

will be damaging to the

feet and legs. So make

sure you communicate

with your belayer ahead

of time so you both

understand how much

slack to have in the

rope at that critical

part of the climb.

If you are on a sport

climb, most of the time

the route developer has

engineered the route so

a bolt or two will be

right at the crux

protecting the fall. As

long as you don’t have

too much slack in the

rope, you should be

fine. But remember, the

more rope you have out

the softer the catch

will be. Any falls near

the first couple of

bolts are hard on a

rope. So if at all

possible, switch ends of

the rope after a

substantial fall or give

the rope a few minutes

to recover from the

stretch.

Finally, as you fall,

stay calm (Yeah right!).

Keep your body loose and

be ready to absorb the

impact. Put your arms in

front of you, your palms

to the rock and as you

connect make sure you

don’t hit your head.

Your feet should hit the

rock first. Keep your

knees bent and toes

pointed up, move into

the fall, and use your

legs as a shock

absorber. The more you

successfully fall the

more natural it will

get. What a rush! |

|

TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With the popularity and

increased access to

climbing, fingerboards

are becoming a second

line method of training.

However, we feel that

there are some great

advantages to the

convenience and

specificity of training

boards. Having a board

mounted in a doorway to

a spare room or your

garage makes it easy to

schedule a quick workout

if a little time is all

you have. The specific

nature of fingerboard

training enables you to

gauge your progress much

more effectively than

bouldering at the rock

gym or your home wall.

It is easier to control

if and when you fail

doing a set exercise on

a particular hold on a

board, than if you are

desperately thrutching

for the last hold on

your latest plastic

bouldering test-piece.

This factor will

hopefully permit you to

work to your limits

while minimizing the

chance of injury to your

fingers.

Finger training programs

can be difficult to

figure out. Keep in mind

that what you are

strengthening is

essentially connective

tissue, tendons and

ligaments. It takes a

long time to notice

gains in strength in

this tissue and a very

long time to heal once

it has been injured. If

you are using

fingerboard training in

addition to indoor

climbing on plastic, be

aware of how much stress

you are putting on your

fingers and arms, and be

careful to not over-do

your training. If you

start having problems,

allow yourself time to

heal. If problems

continue, specifically

long-term pain and

swelling in your

fingers, consult a

sports-oriented

physician.

The Training

There are two general

categories of exercises

that you can do on your

Metolius training board.

In simple terms, they

are exercises that build

power or exercises that

build stamina

/endurance.

Endurance-oriented

exercises are a set of

tasks that put your

muscles in a more or

less aerobic state; that

is, training your

muscles to function for

extended periods.

They generally are a

longer duration and a

lower load exercises and

you are maintaining a

lower level "burn" in

the muscles than the

pump you get at the

limit of your strength.

Power-oriented exercises

focus on short duration,

higher load tasks that

your muscles can't

maintain for very long.

With these exercises,

you are building

strength (muscle fiber

size ) and the capacity

to recruit more muscle

fibers for short, quick

bursts of movement.

Any of the training that

follows assumes a good

base strength level.

Most of the work or

exercises that follow

are power-oriented for a

couple of reasons:

-

We feel that you can

develop some

endurance from a

power workout, but

you cannot develop

good power from an

endurance-oriented

workout and in fact,

it is best if they

are trained

independently.

-

It is hard both

physically and

mentally, to hang on

a board for the

extended periods

required to totally

target endurance.

The amount of load you

use for each exercise is

up to you to determine.

We feel the most gains

happen if you use a safe

maximum load for the

cycle that you are in.

Try to pick a load that

allows you to barely

hold on for the time

indicated in the

exercise. Load is

determined relative to

your body weight. If you

need to add weight, use

a weight belt. If you

need to reduce weight,

use a chair or step

stool set back from and

under the board that

allows you push with one

leg. Make sure your

other leg stays below

you, so that if you

fall, you land on your

feet. You can use a

bathroom scale on a

chair to give you a more

accurate idea of how

much weight you are

taking off (see

illustration). If you

don't feel safe using

this method, have a

partner lift you

instead.

Use Partners

Partners can check

your time and remove or

add weight as well as

give you assistance and

cheer you on when you're

trying to get that last

bit of effort out.

Having a partner spot

you when training to

absolute failure is

highly recommended.

Setup A Workout

Schedule & Stick To It

Make a chart and use it

to keep track of your

training. If you keep a

detailed record showing

amounts of weight and/or

assistance for each

segment of an exercise,

it will be much easier

to slowly increase your

workload. These records

will help you get the

most benefit from your

training time.

Use Any of the Holds

For Any Exercise

You will probably find

that certain holds are

better suited to certain

exercises than others.

For example, you would

probably do pull-ups on

different holds than

short duration hangs. It

is also important to

look at your weakest

points and train those

first. For example, if

you have a hard time

holding onto sloping

holds, focus your

training there early in

your workouts. It is

also a good idea to

change the holds you use

for a given exercise

every few weeks, to

maximize the

effectiveness of your

training.

Dos & Don'ts

Avoid doing an excessive

number of pull-ups on

your board. A lot of

pull-ups on a static bar

can lead to elbow joint

injuries. If you wish to

do more pull-ups than

our exercises indicate,

we recommend that you

use Metolius Rock Rings.

Avoid range of motion

exercises for your

fingers on any training

board. Once you place

weight on a hold do not

attempt to move your

fingers (don't do mini

pull-ups with your

fingers) as this can

lead to injury.

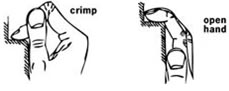

Avoid using crimp or

cling grips. A very

important aspect

concerning any hold is

how you hold on to it.

It is extremely

important that you do

not use any kind of

cling technique

regularly. Because of

the increased angle of

your fingers while

clinging, the load on

your finger joint is far

too high to be safe for

training purposes. We

have found that if you

keep your hand more

open, you will be safer

and still can strengthen

your fingers for both

open-handed and cling

holds. The illustration

pictured shows both

types of holds. Use

chalk when training and

occasionally clean your

board with a nylon brush

to maintain a consistent

surface.

The Tasks

Following are the basic

elements of exercises

that can be done on your

training board:

-

Hangs - either

straight arm or bent

arm, one arm or

both. When hanging

straight, there

should still be a

slight bend to the

elbows.

-

Pull-ups - can be

done with the hands

parallel or offset (

one of your hands on

a higher or smaller

hold than the

other). Offset pulls

put more training

stress on the higher

or smaller hold arm

and can more

effectively simulate

certain climbing

situations.

-

Knee Lifts - Hang on

good holds and bring

your knees to your

chest, bending at

the waist and knees.

This task works the

often overlooked

abdominals for that

solid mid-body

connection.

-

Shoulder Shrugs -

Hang as above and

raise and lower your

body without bending

your elbows. This

exercise works

several different

muscle groups in the

shoulder girdle. As

with pull-ups, we

would recommend

keeping repetitions

low.

Cyclic Periodization

As an overall strategy,

cyclic periodization

allows you to be at your

peak when you want to

be. Whether this

corresponds to a big

road trip or pushing

your limits when the

weather is the best is

up to you. If properly

done chances of injury

and mental burnout are

minimized and gains in

strength and power are

optimized.

The concept is simple;

build a base of

endurance then work

toward maximum power. By

pushing your body in

these cycles you strike

a balance between

letting yourself be

fresh and strong within

the cycles and not

letting yourself totally

adapt to the stresses of

the workouts. This keeps

you from stalling at

different plateaus and

makes the gains possible

much greater than doing

the same sets of

workouts month after

month. Immediately

following the peak cycle

you should be ready to

climb strongly. |

|

TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aid Climbing by

pulling or resting on

gear that is either

placed or fixed into the

rock. This is in

contrast to free

climbing. Aid routes are

also called "nail ups."

A route which requires

aid climbing is rated

grade 6 (free climbing

is rated grade 5, as in

5.10).

Anchor The point

where a climber's rope

is securely attached to

the rock.

Backstep This

foot technique uses the

outside of the shoe on

an edge.

Barndoor A poor

example of balance.When

the climber loses grip

with the hand and foot

on one side and they

fall sideways as if on a

hinge of the opposite

hand and foot.

Belay Use of a

rope to protect a

climber against a fall.

A climber can be belayed

by another person, or be

climbing alone, using an

advanced technique

called a self-belay.

Belay Device A

device used by the

belayer which acts as

the brake on the rope.

Some examples are figure

8's, ATC's and GriGri's.

Bivouac A camp,

or the act of camping.

On a big wall, camp can

be made on a natural

ledge or an artificial

one, generally an

aluminum and nylon

cotlike device called a

portaledge that hangs

from one or more anchors

on the wall. Also called

"bivy".

Bolt Literally a

bolt drilled into the

rock face.

Boulder A style

of climbing which

involves climbing only

at a height the climber

feels comfortable

jumping to the ground.

Bucket A large

hand hold. Feels as

secure as a rung on a

ladder.

Carabiner An oval

or D-shaped link of

lightweight aluminum or

alloy that serves as the

climber's all-purpose

connector.

Chimney A wide

crack that accommodates

(most of) the body of

the climber.

Clean The act of

removing any non-fixed

protection from the

rock.

Crag A climbing

area, usually a cliff.

Crank To pull on

a hold as hard as you

possibly can.

Crater To fall

and hit the ground

pretty hard.

Crimper A very

small hold which allows

only finger tips, if

that.

Crux The hardest

move, or series of

moves, on a climb. The

rating of a climb is

generally that of the

most difficult move.

Deadpoint A

dynamic move which

involves precision

movement in order to

catch the hold at the

peak of the move before

momentum waivers and

gravity starts taking

over.

Edging Climbing

technique when climber

places edge of shoe

precisely on top of a

hold or unconformity on

the rock.The opposite of

smearing.

Figure Eight A

device shaped like an 8

used for belaying and

rappelling.

Free Climbing

using only hands and

feet to move upwards.

Unlike Aid Climbing,

free climbing uses the

rope and gear only as

protection against a

fall, not as a ladder

for upward movement.

This method also

stresses the use of gear

that is temporarily

placed in the rock for

protection by the

leader, and then removed

by the second climber.

Gripped Frozen

from fear.

Haul Bag Large

and robust bag used to

haul food, water,

climbing gear, sleeping

bag, and more up a big

wall. Also known as "the

Pig" since it is

comparable in size and

possibly in weight.

Indoor Public

climbing gyms and

homegrown climbing walls

have been around for

about a dozen years now.

These artifical

environments substitute

the bumps, cracks and

other irregularities

found in natural rock

with a vast assortment

of cast fiberglass

holds. The holds, some

as small as silver

dollars and others as

large as a gallon milk

jugs, are bolted to

plywood walls in random

patterns. The walls

themselves can be sloped

in or out and arranged

to form inside and

outside corners,

overhangs, cracks and

other common climbing

situations.

Jumar is the

method of climbing a

rope using ascending

devices that can be

quickly attached and

then loosened from the

rope. Jumar is the name

of the device (sliding a

knot of rope or webbing

up a rope is called

Prusiking, after Dr.

Karl Prusik); Jumaring

is the act of ascending

the rope.

Layback A

climbing technique where

hands and feet work in

opposition as one scales

a crack or flake.

Mantel A climbing

move which looks like a

small child climbing up

to the kitchen counter.

Hand(s) are on ledge,

one foot comes up, as

you rock over one hand

with your elbow locked.

Mountaineering At

one end of the spectrum,

mountaineering can

include peak bagging,

where little or no

technical skills or

equipment are needed to

reach the summit of a

mountain. It can also

include full-blown

expeditions to the

highest peaks and the

worst weather conditions

on Earth. Generally,

though, mountaineering

adds specialized ice

climbing skills and gear

to those of rock

climbing. Mountaineering

also tends to be

destination oriented.

On-Sight Similar

to flash which means

climbing without any

falls. The difference

being it is the first

time the climber has

ever seen the route.

Pig Also known as

Haul Bag. Large and

robust bag used to haul

food, water, climbing

gear, sleeping bag, and

more up a big wall.

Pitch The section

of rock between belays.

Generally, pitches are

no longer than the

length of the rope (165

feet). Many sport climbs

are set up so that their

anchors are only half

the length of a standard

165-foot rope from the

ground, so that climbers

need only a single rope

in order to be lowered

or to rappel off the

climb.

Quickdraw A pair

of carabiners connected

with a short piece of

webbing. A quickdraw is

used to quickly connect

a climber to a piece of

pro or a permanent

anchor.

Rack The full set

of gear needed to climb

a route.

Rappel Using a

rope to descend from a

climb. Modern rappels

are generally done with

a rappel device, which

creates friction on the

rope to help control the

descent. Also called

abseiling.

Redpoint When a

climber has led a climb

from top to bottom with

out weighting the rope

or gear. Also called a

clean ascent. In the

1980s, German climber

Kurt Albert marked

climbs which he had done

with no falls with a

redpoint at their base.

Sidepull Vertical

slot hand hold which is

pulled on from the side

instead of downwards

like most holds.

Simul-climb When

both the leader and

partner are both

climbing at the same

time, connected by a

rope. This is done on

easy terrain, or if the

rope is too short to

reach a belay. Many

times simul-climbing is

done using a running

belay (the leader places

protection, which is

removed by the second)

rather than fixed

anchors at the end of

each pitch or rope

length.

Smearing Climbing

technique in which the

climber attempts to

stand on the rock by

getting as much friction

as possible between his

shoe and the rock.

Generally this involves

placing the sole or toe

of the shoe directly on

top of the hold or rock

surface, then pushing

and twisting the foot.

The opposite of edging.

Soloing When a

climber ascends without

a partner, rope, or

equipment to protect him

from a fall. A "rope

solo" is when a solo

climber uses a rope to

self-belay. Simul-soloing

is when two climbers

solo together without

the benefit of a rope.

Sport climbing is

different from

traditional in that the

climber depends on fixed

bolts rather than

removable protection.

Sport climbing routes

often follow seemingly

impossible paths,

sometimes straight up

huge, smooth rock walls,

sometimes far out on

horizontal overhangs.

The emphasis in sport

climbing is usually more

on technique than

topping out. Falls are

frequent, though seldom

serious, as climbers

constantly push the

limits of gravity and

ability.

Top Roping

Pre-protecting a climb

from above. The belay

for a top roped climb

can either be from the

top of the pitch or the

bottom. Climbs can be

led, then top roped or

protected by hiking to

the top and fixing the

anchor.

Trad or

traditional climbing

requires a leader to

place his own

protection, rather than

merely clipping into

bolts. The term gained

popularity in the late

1980s with the

development of sport

climbing routes (climbs

that were pre-protected

with bolts).

Traditional rock

climbing involves the

use of ropes and

temporary anchors to add

a degree of safety to

the sport. As the lead

climber ascends the

rock, he or she inserts

an assortment of metal

anchoring devices, known

collectively as

protection, into the

cracks and crevasses at

points that may be

anywhere from a few feet

to several yards apart

depending on the

difficulty of the route.

With the protection

securely in place, the

climber then uses a

carabiner to attach the

rope. Once the rope is

clipped to a piece of

"pro," the belayer below

is responsible for

tending the rope and

stopping the climber in

the event of a fall.

Undercling A hand

hold which is upside

down and is used by

pulling up against it

instead of pulling down.

Whipper A fall,

usually a very long one.. |

|

TOP |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|